Moose (Alces alces) are found in a variety of habitats throughout the boreal forest and non-forested landscapes of Saskatchewan. In the boreal forest, moose select different habitats throughout the year and require a diversity of forest landscapes to meet their various needs.

What's happening

What we are doing

Moose use landscapes that are a mixture of closed, mature coniferous stands for cover from both heat and cold, young regenerating deciduous areas for browsing, and aquatic foraging areas in the summer. The need for cover and availability of forage are primary considerations in moose habitat selection, making landscapes with a mixture of these habitat types most suitable.

Moose benefit from disturbances in the forest, such as fire and logging activities, due to the abundance of young forage associated with forest regeneration. They may also be negatively impacted by forestry activities through the opening of roads in areas previously free from vehicle access and linear disturbance. The impacts of linear disturbances and logging activity result in fragmentation of habitat, increased and improved access for humans and predators, and disruption of travel corridors. There is also a higher risk of predation associated with larger clearcuts where the distance to cover is increased.

In the boreal forest, hunter success can be influenced not only by the availability of moose, but also by increased access from new roads and changes in animal behaviour in response to areas with high hunting pressure (avoidance behaviour). Also, advances in hunting equipment allow greater access and precision and therefore greater success. As access increases, hunter success may stay the same or increase, despite a drop in population.

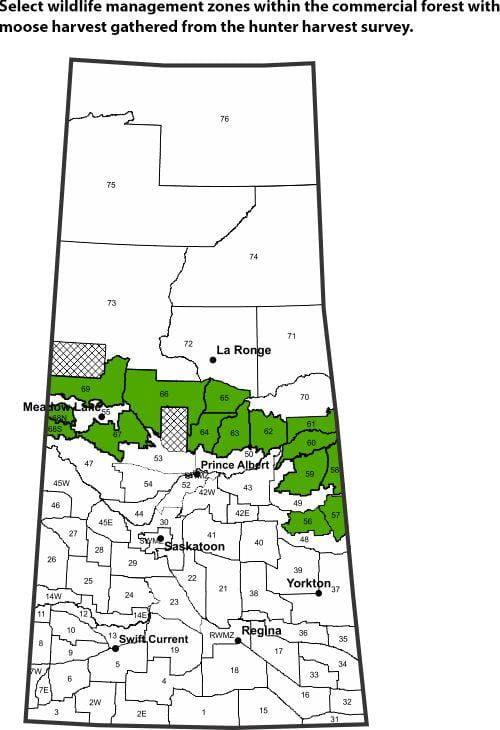

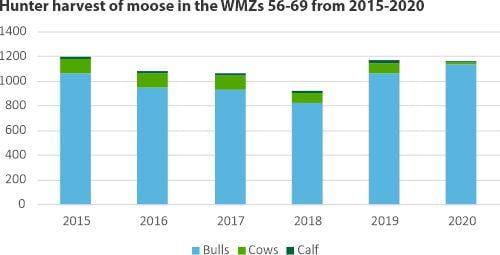

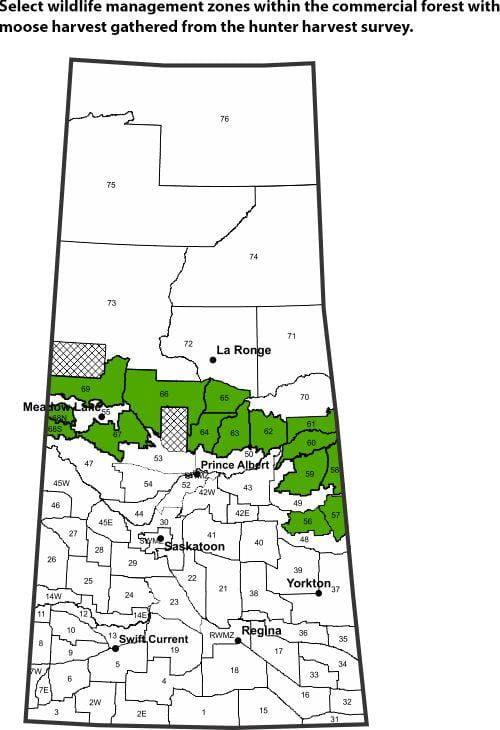

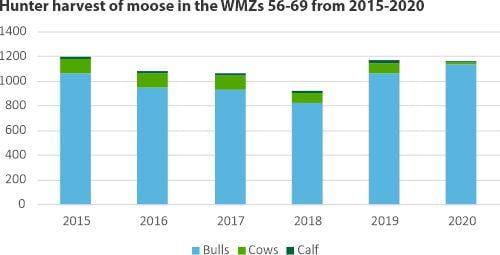

Hunter harvest success is calculated from the number of animals harvested per hunter who submitted a hunter harvest survey. Response rates vary from year to year, but are generally around 25 per cent. Hunter harvest was assessed in 15 wildlife management zones between 2015 and 2020. Hunter harvest success can be a useful population measure when used with other information sources, including aerial surveys and anecdotal information gathered from hunters and conservation officers who spend significant periods on the land observing wildlife and hunter dynamics.

Based on aerial surveys, moose in the southern commercial forest wildlife management zones are declining. Anecdotal information and reports from field staff have confirmed similar trends across all the southern boreal forest wildlife management zones.

Moose populations have been declining across North America, including the southern portions of Saskatchewan's commercial forest. For example, a 2018 aerial survey in WMZ 67 showed a 30 per cent decline from a survey 10 years earlier. A 2004 aerial survey of WMZ 67 showed an estimated population of 2,021 individuals (+/- 25.1 per cent) and the 2018 survey showed a population estimate of 1,340 individuals (+/-19.4 per cent). This means that there are less than half as many moose per square kilometre now, compared to 2004.

A variety of factors may contribute to the current population declines in the southern portions of the commercial forest. Habitat change, disease, parasites, increased access leading to elevated risk from predators and hunters can all contribute to moose population decline. Further study is required to evaluate the current moose population and understand this regional decline.

Why it matters

Moose are a high-value species to all hunters in Saskatchewan. They are an important component of the diet and culture of Indigenous people along the forest fringe and southern boreal forest. Resident and non-resident moose hunting contributes significantly to local economies throughout the province. In 2020, there were 6,448 regular licences and 4,999 draw licences sold for moose. Outfitting for non-Saskatchewan residents is authorized in the province, with approximately 300 guided moose licences available annually.

The ministry is taking steps to better understand forest moose populations with a moose survey planned for WMZs 56 and 57 in early 2022, which will help inform population trends. A moose research project is also planned for fall 2021 in the east-central part of the province, where cow moose will be radio-collared. This will allow wildlife managers to determine cause-specific mortality of cow moose and help inform management direction. Moose populations have been declining in a number of jurisdictions in the last decade. Manitoba saw severe moose declines that led to a total closure of hunting in multiple regions of the province in 2011 and again in 2015. Closures were still in place for Manitoba's 2020 hunting season, and populations are still below desired levels, though a halt in decline and a slight increase has been observed since closing hunting seasons. British Columbia experienced severe moose declines in 2013-14 that were observed through aerial surveys. Minnesota moose populations were also declining steeply from 2006 through 2017 (approximately 60 per cent), but declines have levelled out as of 2018. A four-year study in Minnesota showed that major sources of mortality included parasitic infections, wolf kills and compounding factors such as underlying health problems that may have contributed to higher wolf kills.